Geometric Flows

I undertook a research project (UROP) under the supervision of Prof. Fredrick Fong, along with a research group, in summers of 2024. I studied the topic of “Geometric Flows” - mostly studied the Hamilton and Cage "The Heat Equation Shrinking Convex Plane Curves" paper. At the end of the project, I wrote a summary report that you can view here.

Although I spent a larger time studying manifolds in differentail geometry, I did not include that in my report as my report was mainly about Curve Shortening Flows (generalized to Mean Curvature Flow) and I did not end up using the properties of manifold I studied. As such, I only intend to give an introduction into the contents of my research report. I made some notes along the way on interesting things that were not in the resoureces being studied, you can also view my notes here - although it should be pretty useless to anyone but me (credits to the horrible organization and lazy writings).

Introduction

I am not sure of the formal defintion of “Geometric Flows” - however, in our studies we particularly studied the Curve Shortening flow.

Here’s the idea: we start with some closed smooth curve and overtime the curve evolves according to the following rule : At each point in time, each point is moving towards it’s normal vector (in the direction of the curvature) with the speed of it’s curvature. Formally, this can be described by the equation:

\[\frac{\partial \gamma}{\partial t} = -k N\]“Curvature” is intuitive how sharply the curve turns - a straight line for example has curvature 0 at each point.

Here’s a website that simulates this flow for any curve you draw into it, feel free to play around : https://a.carapetis.com/csf/

Convex Curves

Convex curves are nice curves because “they do not go too crazy”. As one would expect, convex curve has some nice properties that makes it easier to study CSF for those curve. Therefore, the report starts witth analysing some of these properties for example the sum (or rather the integral) of the tangent vector is 0

\[\int_{0}^{2\pi} T(\theta) d\theta = 0\]Simlarly, the total curvature of any closed convex curve is \(2\pi\). The curvature always points inward and If we restrict ourselves to strictly convex curves, then the curvature is also non-zero.

It also turns out that we can parametrize any convex curve with just one variable \(\theta\) - the angle the tangent vector makes with any chosen fixed line. This can not be possible with concave curves that can just turn out (making a hole) and achieve the same angle at the different time.

Properties of CSF

On Convex Curves

After taking a look at convex curves, we see how the flow reacts to these curves. We start by analysing the arclength and the area to show that this flow is certainly “shortening” - that is, it eventually terminates by shrinking to a point. An interesting result from this section is that the rate of decrease of area is actually equal to \(-2\pi\) !

After that, we show that any convex curve remains convex until it reaches singularity.

On Concave curves

The Hamilton and Cage paper only deals with convex curves - however I was qutie interested in also taking a look at concave curves. Things can get messy in concave curves as we do not have much control over the curvature - for example, a concave curve can have self intersection - or evolve into a slef intersecting curve.

It turns out that every concave curve eventually evolves into a bunch of convex curves. This amazinng result is achieved by Grayson’s theorem, that genralizes the Cage-Hamilton Theorem :

” Grayson’s Theorem “

Convergence to a round point is given by the existence of a unique point \(x_0 \in \mathbb{R}^2\) such that the rescaled flows \(\gamma_t^{\lambda} = \lambda \cdot (\gamma_{T + \lambda^{-2}t} - x_0)\) converge as \(\lambda \to \infty\) to the round circle \(\{\partial B_{\sqrt{-2t}}\}_{t\in(-\infty, 0)}\) which shrinks. If the initial curve \(\gamma_0\) is closed embedded cruve, then the curve shortening flow >converges to a round point.

This is really nice since we can now use similar analysis to concave curves!

Bounds on time

We next explore a couple of time bounds for \(T\) - the time taken to reach singularity. We bound \(T\) by area, arlenght and curve. Essentially, the motivation behind this was just to get the invariance of inscribed curves.

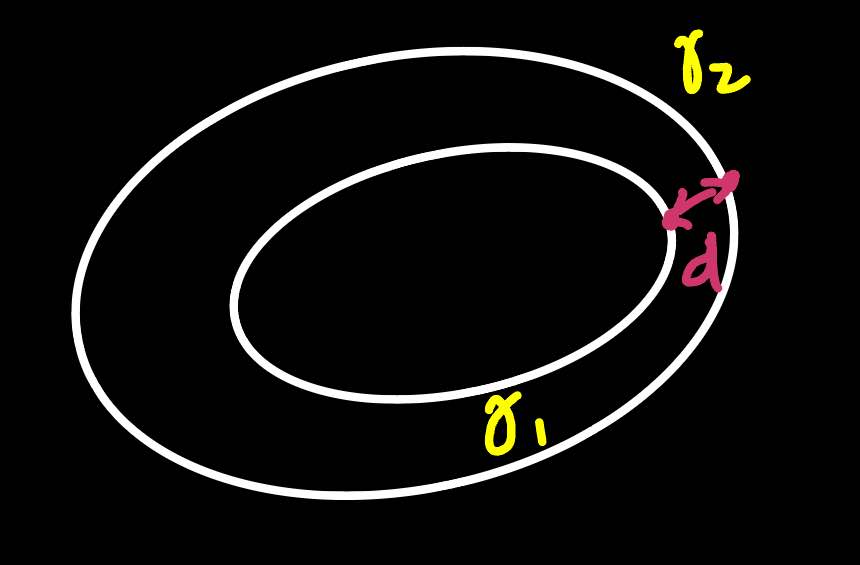

If you inscribe the curve \(\gamma_1\) inside \(\gamma_2\), which formally means for \(t \in [0, min(T_1, T_2))\),

\[d(t) = \inf || \gamma_2(t) - \gamma_1(t) || \geq 0\]It turns out, that \(\gamma_1\) will always remain inside \(\gamma_2\) (before reaching singularity). The idea here is just to consider the minimum time \(t_0\) such that \(d(t_0) = 0\) and use maximum principle to argue that at this point, \(k_{\gamma_1}(p_1) \geq k_{\gamma_2}(p_2)\). Consider the equations of evolution, these two points can not “cross” each other \(\implies \gamma_1\) remains inscribed inside \(\gamma_2\).

Closing Remarks

Overall, this was a great first expereince for me at hands on pure math research. Although I do not like studying manifolds - since it’s seemed quite uninspiring to me - it was quite fun to study CSF and particularly enjoying to discover properties outside of the provided resources on my own. I can’t say I like differential geometry enough to continue research on this, but I would definetly be looking forward to more research experience.